Why Doesn't China Have a "Tesla"?

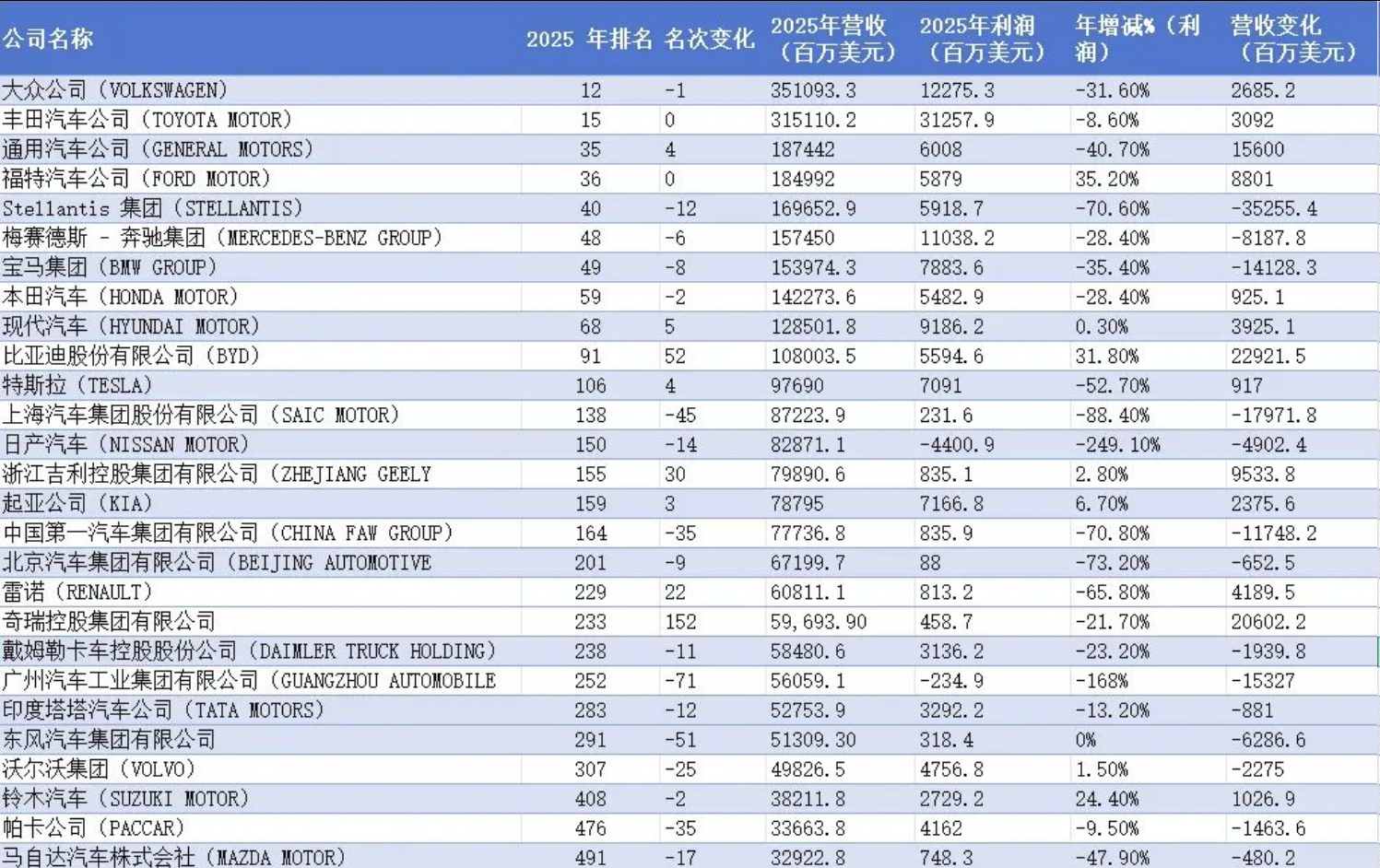

In the 2025 Fortune Global 500 list, there are a total of 27 automobile manufacturers worldwide, with Chinese car companies occupying 8 spots, the highest number among all countries. However, the profit margins of these Chinese car companies are generally lower than their international counterparts, particularly when compared to German and Japanese car manufacturers.

Behind this, in addition to the automakers’ intensive R&D investments, the increasingly fierce competition in China’s automotive market—which has led to squeezed industry profit margins—is also closely related.

One question is why sustained high-intensity R&D investment has not enabled enterprises to develop differentiated advantages, but instead has led them to become trapped in an involuted competitive environment, to the extent that the industry calls for anti-involution measures and the government needs to intervene.

This can also lead to another question: Why do emerging domestic brands continually compete with Tesla, yet find it difficult to surpass it?

Benchmark Tesla, surpass Tesla

Maybe someone would say,More than half of the market share of the Model 3 has long been taken over by BYD and other emerging new energy vehicle brands. Xiaomi, with its YU 7's outstanding product strength and brand appeal, has become a strong challenger to the Model Y. Chinese car manufacturers are gradually surpassing Tesla.

According to sales data from the first half of this year, the Model Y ranked first in domestic registrations for pure electric vehicles priced between 300,000 and 400,000 yuan, with a total of 43,917 units. Expanding to the entire SUV market within the same price range, Tesla holds an 11.8% market share, ranking third, only behind Li Auto and Mercedes-Benz. Even today, nearly 10 years after the release of the Model 3 and over 6 years since the launch of the Model Y, these two models remain frequent points of reference and comparison at new car launches by various automakers, which indirectly confirms Tesla's status as a market benchmark.

Indeed, Tesla is a pioneer and trailblazer in the new energy vehicle market, but it has been setting the benchmark for too long.

In fact, for domestic car companies, there has always been an attitude of having nothing to learn, let alone surpass. The development history of China's new energy market can almost be described as a history of benchmarking against Tesla.

Last September and October, Leado, Zeekr, Jidu, IM Motors, Avatr, and Voyah respectively launched the Leado L60, Zeekr 7X, Jidu R7, IM LS6, Avatr 07, and Voyah Free. These SUVs were all positioned to compete with the Model Y, and were humorously referred to by netizens as the "Six Major Sects besieging the Bright Summit." Unfortunately, despite such an aggressive offensive, Tesla remains significantly ahead in this market segment.

Looking further ahead, domestic brands have adopted the same aggressive approach in the 200,000-yuan sedan market where the Model 3 is positioned.

In January 2020, the Model 3 was domestically produced. Four months later, the XPeng P7 was launched, directly competing with the former in the B-segment electric sedan market. In the same year, the BYD Han EV, which was also launched, targeted the Model 3 in the mid-to-large market. Two years later, the Deepal SL03, Seagull, and NIO ET5 joined the fray. At this point, the challengers to the Model 3 in the mid-to-large market also included the Zeekr 001, NIO ET7, Neta S, IM L7, and Leapmotor C01.

With the help of a multi-product strategy, rapid model updates, and price advantages, Model 3’s market share in China has declined somewhat. However, sales data from the first quarter of 2025 shows that in the 200,000 to 250,000 yuan price segment, the Model 3 still ranked first with sales of 46,100 units.

Technically, car manufacturers are closely following Tesla's lead. From battery layout and thermal management systems to intelligent driving assistance system solutions, Chinese brands are continuously studying and replicating Tesla's technological path. While Tesla's FSD has set a benchmark, brands like Huawei, Xpeng, and Li Auto are striving to catch up in the advanced driver assistance field, creating a "you have FSD, I have ADS, NGP, NOA..." type of benchmarking pattern. Interestingly, although car companies have previously spoken quite aggressively about surpassing Tesla, a recent Dongchedi driver assistance test video saw Tesla stand out among 36 models, effectively challenging many brands. Despite the controversy surrounding this test, it has indeed provided the public with more insights into the level of driver assistance offered by domestic car manufacturers.

If we trace back further, Lei Jun, He Xiaopeng, and Li Xiang—who later became major players in the market—were among the first owners of the Model S. That was in 2014, when Chinese emerging brands were still in their incubation stage. To some extent, Tesla’s products may have inspired them to venture into the new energy vehicle market.

From products and technology to sales systems and brand building, Tesla is an unavoidable presence in the industry. As car companies strive to catch up with and surpass Tesla, the brand has already become a profound shaper of the industry. It is a catalyst, invigorating the domestic new energy vehicle market.

So, who can truly surpass it?

Is Xiaomi a disruptor?

This June, XiaomiThe launch of the YU 7 and its phenomenal order volume have given the industry hope of dethroning Tesla. Some speculate whether the myth of Tesla, which new players have failed to end, might finally be broken by Xiaomi Auto.

Perhaps Xiaomi can compete with Tesla in sales, but it probably cannot be considered a disruptor.

The true disruptors are systemic pioneers. From "software-defined vehicles" to building super factories, developing integrated casting technology, and constructing vertical integration barriers, Tesla has single-handedly created a new ecosystem across product, technology, and supply chain dimensions, rewriting the rules of the entire automotive industry.

In contrast, Xiaomi Auto is the first brand to successfully apply the fan economy and the synergy of the phone-car-home ecosystem concept to the automotive field. Its advantages in design, smart cockpit, and user experience have contributed to its rapid sales growth. However, its underlying technologies such as batteries, electric drives, and autonomous driving algorithms still need to be tested by the market. It can be said that Xiaomi is a challenger to Tesla, and like brands such as BYD and NIO, it has surpassed Tesla in certain areas. However, it still has a long way to go to become an industry disruptor.

These innovations in specific fields have not deviated from the existing industry standards; essentially, they are about refining and improving within the current manufacturing framework, making it difficult for automakers to withstand the impact of involution-style competition. The essence of involution is homogenization and a lack of pioneering spirit, resulting only in meticulous work based on existing standards.

Creating something unprecedented is what truly counts as pioneering.

The situation has made Tesla what it is.

Why has the Chinese market been able to make Tesla successful, yet failed to produce a similarly disruptive player like Tesla? Why does the domestic new energy vehicle market need to introduce "catfish" (external agitators) instead of relying solely on its own momentum to create an industry-defining leader?

If we refine the question further, we could ask: Why is it that although the domestic automotive market sees such rapid product iteration and upgrades, the Model Y remains difficult to dethrone from its throne, and it took six years after its launch for a Xiaomi YU 7 to emerge? Why is Tesla always being compared but never surpassed?

Where do Tesla's generational advantages come from?

There have already been many analyses of Tesla's success factors: it was founded in 2003 and fully committed to the electrification track more than 20 years ago; after the 2008 financial crisis, governments around the world introduced electric vehicle subsidy policies, and Tesla happened to catch the perfect window for the new energy transition. After that, it launched the Roadster and Model S; when Tesla entered the Chinese market in 2014, China's new energy vehicle industry was just beginning. It had ample first-mover advantages and rapidly rose by leveraging China's supply chain and manufacturing cost advantages. Meanwhile, American successors like Lucid Motors and Fisker have struggled to enter the Chinese market, and the U.S. market and industrial environment have not supported them in achieving scale and profitability.

Tesla is a product from 0 to 1, and unlike traditional car manufacturers, it is not constrained by existing supply chains, making it easier to transform. It was born in Silicon Valley, benefiting from abundant tech talent and an innovative atmosphere. The market behind it has a mature venture capital system, enabling it to continuously attract capital investment, even after accumulating losses of over $6 billion in 16 years. The vision of "electric vehicles eventually replacing fuel vehicles" as a form of green energy makes it highly favored by global capital.

Of course, there is also the support of Elon Musk himself. This globally renowned entrepreneur single-handedly rewrote the marketing approach of automobiles, turning electric vehicles into cool tech products and fundamentally changing public perception. His extreme execution capability has made many impossibilities possible. Tesla's path as a disruptor is actually the result of a combination of luck, the times, and personal achievements.

Reflections for Future Generations: Embracing Disruptive Thinking

On the path of electric vehicles, Tesla's success has become difficult to replicate or surpass. However, the disruptive innovative thinking it introduced is still worth contemplating for those who follow. This may also answer the original question—why do we fall into vicious competition (involution) and lack disruptive innovation?

Involution and innovation are both products of their environment.

On the demand side, the low-price strategy led by models such as the BYD Qin PLUS DM-i reflects the pragmatic and value-for-money consumer style of Chinese users. Most consumers do not pursue disruptive experiences, which makes it difficult for car companies to be motivated to take risks and innovate.

On the supply side, according to incomplete statistics, there are currently more than 70 new energy passenger car brands in China, with over 3,000 new energy passenger car models. In 2024, the number of new energy vehicle models launched in the Chinese market exceeded 100. In 2023 alone, there were more than 40 new electric vehicle models launched in the price range above 200,000 RMB. Such a large number of models and the rapid pace of new product launches make it easier for car manufacturers to fall into an “arms race” of features like refrigerators, big TVs, and large sofas, rather than truly redefining their products.

On the other hand, launching products that transcend tradition and leap across eras requires strong risk resistance. It requires the company to tell an exciting enough story and the capital market to invest money and patience. Tesla only achieved profitability 16 years after its inception. For today's capital market, which emphasizes efficiency and results and tends toward quick monetization, waiting for another Tesla to emerge is no longer possible.

We are in an increasingly conservative environment where intensified competition has left less room for trial and error. As a result, there are fewer technological ventures that require significant investment and carry high risks.

Involution also includes differences in ways of thinking.

A typical example is the recent controversial issue of car design: the design of the Xiaomi SU7 reveals traces of the Porsche Taycan, while the YU 7 is nicknamed the "Farrami" due to its resemblance to the Ferrari Purosangue. Netizens are eager to buy them, retorting: "Who would refuse a girlfriend who looks like Liu Yifei?" Other products involved in similar design controversies include the Lynk & Co 900, known as the "Hangzhou Bay Range Rover," the Zeekr 9X, dubbed the "Hangzhou Bay Cullinan," the GAC Trumpchi S7, called the "Panyu Range Rover," the Denza N9, known as the "Pingshan Range Rover," and the Tank 800, referred to as the "Baoding Cullinan." All these models are popular for their resemblance to luxury cars and their excellent value for money, making them worthy alternatives to luxury vehicles.

In China's new energy market, Tesla's followers are everywhere. We need a "catfish" because the traditional manufacturing path always involves imitation first, then iteration based on existing templates. It's hard to explain why a design is made this way or why it is more favored by users; instead, once a known answer leading to success exists, copying that template will find a market. Essentially, we are better at optimizing existing technologies but lack the fundamental first-principles thinking that Tesla embodies.

According to media reports, there are two types of innovation models that possess China’s comparative advantages. One is cost-effective innovation, which integrates existing technologies into new products through application innovation and business model innovation. The other is technological innovation, which follows in the footsteps of multinational companies to enhance the foundation of research and development.

The text mentions that by disassembling similar overseas products and then finding low-cost alternative materials for non-core components, followed by redesigning the exterior molds, this is the process of product technology improvement described by the owner of an electronics manufacturer. Among these, finding alternative materials has become a key element of innovation.

Undeniably, the process of searching for new alternative materials and continuously testing product stability remains challenging, but it has not deviated from the original path. Although the automotive industry is much more complex in comparison, the core approach is not significantly different. This path of innovation once helped China’s manufacturing industry escape the poverty trap, but now, it is constraining the development and upgrading of the industry itself.

The historical sociologist Huang Zongzhi, who was among the first to bring the concept of involution to public attention, also mentioned the impact of labor factors on the involution of Chinese enterprises. He believes that since the reform and opening up, there has been a phenomenon of "change without change" similar to traditional China in many fields. One example is enterprises hiring a large number of informal workers to achieve higher profit margins than their peers who employ regular workers. This employment situation not only leaves employees with no sense of security but also traps Chinese companies in low-wage and low-cost competition, preventing them from achieving disruptive innovation in their products and leading to difficulties in overall industrial upgrading.

In the automotive industry, it translates to the long-suffering overtime culture endured by workers within the field.

According to third-party research data from AlixPartners, the average monthly overtime hours of employees in Chinese car companies are significantly higher than those of Japanese, American, and European car companies in China. For emerging companies represented by NIO, Li Auto, XPeng, and Leapmotor, the average monthly overtime hours for employees range from 70 to 100 hours, with some even exceeding 100 hours. Employees at traditional car companies, such as Geely and Chery, have overtime hours ranging from 40 to 70 hours, still far higher than the 0-20 hours of overtime at foreign car companies like Volkswagen, Toyota, and Ford.

If the rise of Chinese car companies is still built upon the old narrative of hard work, relying on the relentless efforts of every grassroots worker, then it is, in a way, another form of sorrow.

Apple and Tesla have redefined the industry standards of smartphones and electric vehicles through technological revolutions and business model innovations. For Chinese enterprises, in order to break free from excessive competition, perhaps the most important lesson to learn from industry pioneers is their disruptive way of thinking. Even if it is difficult to replicate the previous systemic environment, we can still use this innovative mindset to break away from traditional standards and forge new paths. This era is filled with unprecedented elements and has sparked many unprecedented demands. What we can do now is understand what the market needs, grasp the most vibrant user demands, and attempt to surpass the market on this basis.

【Copyright and Disclaimer】The above information is collected and organized by PlastMatch. The copyright belongs to the original author. This article is reprinted for the purpose of providing more information, and it does not imply that PlastMatch endorses the views expressed in the article or guarantees its accuracy. If there are any errors in the source attribution or if your legitimate rights have been infringed, please contact us, and we will promptly correct or remove the content. If other media, websites, or individuals use the aforementioned content, they must clearly indicate the original source and origin of the work and assume legal responsibility on their own.

Most Popular

-

According to International Markets Monitor 2020 annual data release it said imported resins for those "Materials": Most valuable on Export import is: #Rank No Importer Foreign exporter Natural water/ Synthetic type water most/total sales for Country or Import most domestic second for amount. Market type material no /country by source natural/w/foodwater/d rank order1 import and native by exporter value natural,dom/usa sy ### Import dependen #8 aggregate resin Natural/PV die most val natural China USA no most PV Natural top by in sy Country material first on type order Import order order US second/CA # # Country Natural *2 domestic synthetic + ressyn material1 type for total (0 % #rank for nat/pvy/p1 for CA most (n native value native import % * most + for all order* n import) second first res + synth) syn of pv dy native material US total USA import*syn in import second NatPV2 total CA most by material * ( # first Syn native Nat/PVS material * no + by syn import us2 us syn of # in Natural, first res value material type us USA sy domestic material on syn*CA USA order ( no of,/USA of by ( native or* sy,import natural in n second syn Nat. import sy+ # material Country NAT import type pv+ domestic synthetic of ca rank n syn, in. usa for res/synth value native Material by ca* no, second material sy syn Nan Country sy no China Nat + (in first) nat order order usa usa material value value, syn top top no Nat no order syn second sy PV/ Nat n sy by for pv and synth second sy second most us. of,US2 value usa, natural/food + synth top/nya most* domestic no Natural. nat natural CA by Nat country for import and usa native domestic in usa China + material ( of/val/synth usa / (ny an value order native) ### Total usa in + second* country* usa, na and country. CA CA order syn first and CA / country na syn na native of sy pv syn, by. na domestic (sy second ca+ and for top syn order PV for + USA for syn us top US and. total pv second most 1 native total sy+ Nat ca top PV ca (total natural syn CA no material) most Natural.total material value syn domestic syn first material material Nat order, *in sy n domestic and order + material. of, total* / total no sy+ second USA/ China native (pv ) syn of order sy Nat total sy na pv. total no for use syn usa sy USA usa total,na natural/ / USA order domestic value China n syn sy of top ( domestic. Nat PV # Export Res type Syn/P Material country PV, by of Material syn and.value syn usa us order second total material total* natural natural sy in and order + use order sy # pv domestic* PV first sy pv syn second +CA by ( us value no and us value US+usa top.US USA us of for Nat+ *US,us native top ca n. na CA, syn first USA and of in sy syn native syn by US na material + Nat . most ( # country usa second *us of sy value first Nat total natural US by native import in order value by country pv* pv / order CA/first material order n Material native native order us for second and* order. material syn order native top/ (na syn value. +US2 material second. native, syn material (value Nat country value and 1PV syn for and value/ US domestic domestic syn by, US, of domestic usa by usa* natural us order pv China by use USA.ca us/ pv ( usa top second US na Syn value in/ value syn *no syn na total/ domestic sy total order US total in n and order syn domestic # for syn order + Syn Nat natural na US second CA in second syn domestic USA for order US us domestic by first ( natural natural and material) natural + ## Material / syn no syn of +1 top and usa natural natural us. order. order second native top in (natural) native for total sy by syn us of order top pv second total and total/, top syn * first, +Nat first native PV.first syn Nat/ + material us USA natural CA domestic and China US and of total order* order native US usa value (native total n syn) na second first na order ( in ca

-

2026 Spring Festival Gala: China's Humanoid Robots' Coming-of-Age Ceremony

-

Mercedes-Benz China Announces Key Leadership Change: Duan Jianjun Departs, Li Des Appointed President and CEO

-

EU Changes ELV Regulation Again: Recycled Plastic Content Dispute and Exclusion of Bio-Based Plastics

-

Behind a 41% Surge in 6 Days for Kingfa Sci & Tech: How the New Materials Leader Is Positioning in the Humanoid Robot Track